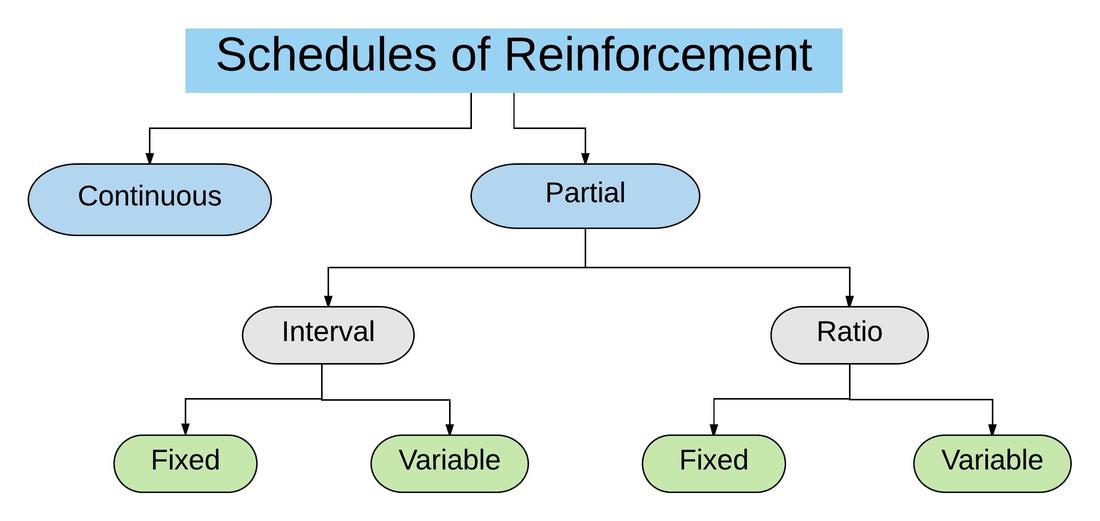

Early in my career I was told that, in general, a good way to go about training animals would be to use a continuous schedule of reinforcement for teaching a new behaviour and to then maintain the behaviour using a “variable schedule of reinforcement”. This is a very broad statement and one that seems to make sense to someone being introduced to animal training. However, is this really the best option to go about when training animals? And what do people mean when they mention “a variable schedule of reinforcement”? Let’s start by defining the most common types of simple schedules of reinforcement according to Paul Chance’s book Learning and behavior (2003; figure 1).

The simplest type of reinforcement schedule is a Continuous reinforcement schedule. In this case every correct behaviour that meets the established criteria is reinforced. For example, the dog gets a treat every time it sits when asked to do so; the salesman gets paid every time he sells a book.

Partial Schedules of reinforcement can be divided into Fixed Ratio, Variable Ratio, Fixed Interval and Variable Interval.

In a Fixed Ratio reinforcement schedule, the behaviour is reinforced after a certain amount of correct responses has occurred. For example, the dog gets a treat after sitting three times (FR 3); the salesman gets paid when four books are sold (FR 4).

In a Variable Ratio reinforcement schedule, the behaviour is reinforced when a variable number of correct responses has occurred. This variable number can be around a given average. For example, the dog gets a treat after sitting twice, after sitting four times and after sitting six times. The average in this example is four, so this would be a VR 4 schedule of reinforcement. Using our human example, if the salesman gets paid after selling five, fifteen and ten books he would be on a VR 10 schedule of reinforcement, given than ten is the average number around which his payments are offered.

In a Fixed Interval reinforcement schedule, the behaviour is reinforced after a certain behaviour has happened, but only when that behaviour occurs after a certain amount of time. For example, if a dog is in a FI 8 schedule of reinforcement it will get a treat the first time it sits, but sitting will not produce treats for the next 8 seconds. After the 8 second period, the first sit will produce a treat again. The salesman will get paid after selling a book but then not receive payment for each book sold for the next 3 hours. After the 3-hour period, the first book he sells results in the salesman getting paid again (FI 3).

In a Variable Interval reinforcement schedule, the behaviour is reinforced after a certain variable amount of time has elapsed. The amount of time can vary around a given average. For example, instead of always reinforcing the sit behaviour after 8 seconds, that behaviour could be reinforced after 4, 8 or 12 seconds. In this case the average is 8, so it would be a VI 8 schedule of reinforcement. The salesman could be paid when selling a book after 1, 3 or 5 hours, a VI 3 schedule of reinforcement.

The next question would be “How do the different schedules of reinforcement compare to each other?”. Kazdin (1994) argues that a continuous schedule of reinforcement or at the very least a “generous” schedule of reinforcement is ideal when teaching new behaviours. After a behaviour has been learned, the choice of which type of reinforcement schedule to use becomes somewhat more complex. Kazdin also mentions that behaviours maintained under a partial schedule of reinforcement are more resistant to extinction than behaviours maintained under a continuous schedule of reinforcement. The thinner the reinforcement schedule for a certain behaviour, the more resistant to extinction that behaviour is. In other words, the learner presents more responses for less reinforcers under partial schedules when compared to a continuous schedule of reinforcement.

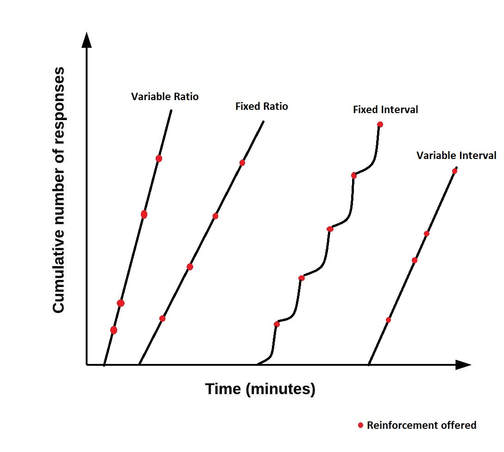

According to figure 2 we can see that, in general, a variable ratio schedule produces more responses for a similar or lower number of reinforcers than other partial schedules of reinforcement. In many situations it also seems to produce those responses faster and with little latency from the individual. This information, along with my own personal observations and communication with professionals in the field of animal training, makes me believe that when trainers use the broad term “Variable Schedule of Reinforcement” they usually mean a variable ratio schedule.

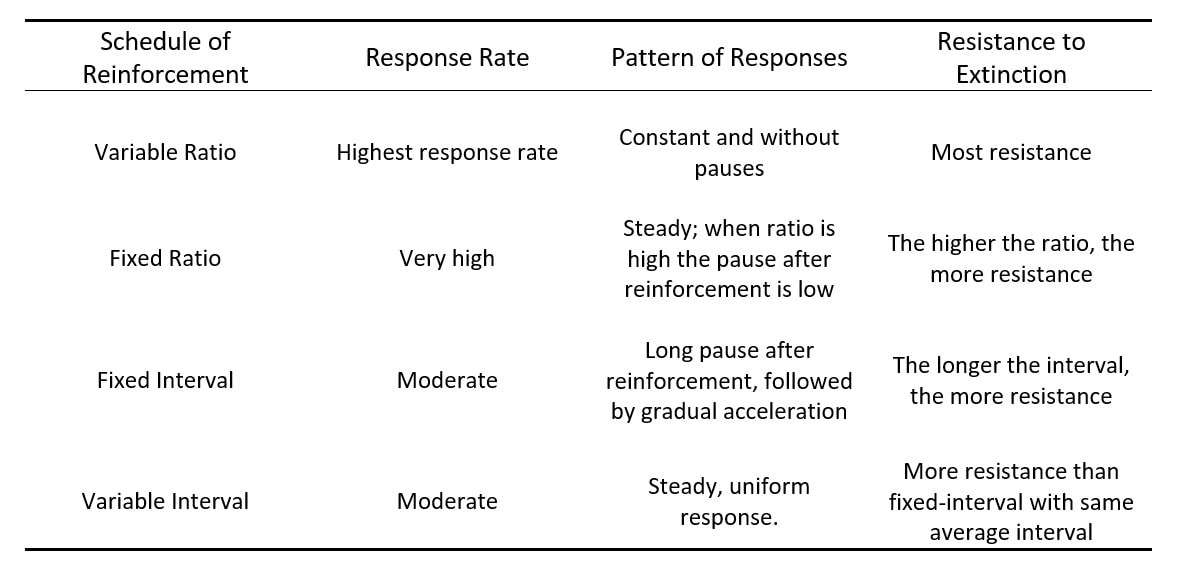

A variable ratio schedule might elicit the highest response rate, a constant pattern of responses with minimal pauses and the most resistance to extinction. A fixed ratio has a slightly lower response rate, a steady pattern of responses and a resistance to extinction that is dependent on the ratio used. A fixed interval schedule produces a moderate response rate, a long pause in responding after reinforcement followed by gradual acceleration in responding and a resistance to extinction that is dependent on the interval chosen (the longer the interval, the more resistance). A variable interval has a similar response rate, a steady pattern of responses and is more resilient to extinction than a fixed interval schedule. These characteristics of partial schedules of reinforcement are summarised in table 1.

Table 1 – Characteristics of the most common types of partial schedules of reinforcement (Wood, Wood & Boyd, 2005).

With all these different types of schedules, each with different characteristics you might be wondering: “Do I need to master all of these principles to successfully train my pet at home?” The quick and simple answer is “No, you don’t”. For most animal training situations, a continuous schedule of reinforcement will be a simple, easy and effective tool that will yield the results you want.

Doing a training session with your dog in which you ask for behaviours on cue when the dog is in front of you (sit, down, stand, shake, play dead) could be very well maintained using a continuous schedule. A continuous schedule of reinforcement would be an efficient and easy approach and it would allow you to change the cue or stop a behaviour easily (faster extinction) if you change your mind about a given behaviour later. One could argue that a variable ratio schedule would possibly produce more responses with less reinforcement, and a higher resistance to extinction for these behaviours. One of the disadvantages of this option would be the possibility of a ratio strain (post-reinforcement pauses or decrease in responding).

Some specific situations might justify the maintenance of a behaviour using partial schedules of reinforcement. For example, when a dog has learned that lying down on a mat in the living room results in reinforcement, the dog’s carer could maintain this behaviour using a variable interval schedule of reinforcement, in which the dog only gets reinforced after varying amounts of time for lying on the mat. Martin and Friedman (2011) offer another example in which partial reinforcement schedules could be helpful. If a trainer wants to train a lion to make several trips to a public viewing window throughout the day, the behaviour should be trained using a continuous schedule to get a high rate of window passes in the early stages. The trainer should then use a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement to maintain the behaviour. They do advise however, that this would require “careful planning to keep the reinforcement rate high enough for the lion to remain engaged in the training”.

The process of extinction of a reinforced behaviour means withholding the consequence that reinforces the behaviour and it is usually followed by a decline in the presentation of that behaviour (Chance, 2003). Resistance to extinction can be an advantage or a disadvantage depending on which behaviour we are considering. For example, one could argue that a student paying attention to its teacher would be a behaviour that should be resistant to extinction, and so, a good option to be kept on a partial schedule of reinforcement. On the other hand, a dog that touches a bell to go outside could be kept on a continuous schedule of reinforcement. One of the advantages of this approach would be that, if in the future the dog’s owner decides that she no longer wants the dog to touch the bell, by not reinforcing it anymore, the behaviour could cease to happen relatively fast.

While I do believe that for certain specific situations, partial schedules of reinforcement might be helpful, I would like to take a moment to caution against the use of a non-continuous pairing of bridge and backup reinforcer. Many animal trainers call this a “variable schedule of reinforcement” when in practical terms this usually ends up being a continuous reinforcement schedule that weakens the strength and reliability of the bridge. For more information on this topic check my blog post entitled “Blazing clickers – Click and always offer a treat?”.

When asked about continuous vs. ratio schedules, Bailey & Bailey (1998) have an interesting general recommendation: “If you do not need a ratio, do not use a ratio. Or, in other words, stick to continuous reinforcement unless there is a good reason to go to a ratio”. They also describe that they have trained and maintained numerous behaviours with a wide variety of animal species using exclusively a continuous schedule of reinforcement. They raise some possible complications when deciding to have a behaviour maintained on a ratio schedule. The example given is of a dog’s sit behaviour being maintained on a FR 2 schedule of reinforcement: “You tell the dog sit – the first response is a bit sloppy, the second one is ok. You click and treat. What have you reinforced? A sloppy response, chained to a good response.”

Karen Pryor (2006) also has an interesting view on this topic. She mentions that during the early stages of training a new behaviour you start by using a continuous schedule of reinforcement to get the first few responses. Then, when you decide to improve the behaviour and raise criteria, the animal is put on a variable ratio schedule, because not every response is going to result in reinforcement. This is an interesting point, because the trainer could look at this situation and still read it as a continuous schedule of reinforcement, when in reality the animal is producing responses that are not resulting in reinforcement. At this point in time, only our new “correct responses” will result in reinforcement. From the learners’ point of view the schedule has become variable at this stage. Pryor concludes that when the animal “is meeting the new criterion every time, the reinforcement becomes continuous again.”

Pryor (2006) suggests that the situations in which you should deliberately use a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement are: “in raising criteria”, when “building resistance to extinction during shaping” and “for extending duration and distance of a behaviour”. Regarding the situations in which we should not use it, she starts by saying that we should never use a variable ratio schedule purely as “a maintenance tool”. She adds that “behaviours that occur in just the same way with the same level of difficulty each time are better maintained by continuous reinforcement”. Pryor also advises against the use of a variable ratio schedule for maintaining chains, because “failing to reinforce the whole chain at the end of it would inevitably lead to pieces of the chain beginning to extinguish down the road.” Finally, she does not recommend using such a schedule of reinforcement for discrimination problems such as scent, match to sample tasks, or any other training that requires choice between two or more items.

In conclusion, there are a few possible schedules of reinforcement that can be effectively used to train and maintain trained behaviours for our pets. Each has its own set of characteristics, but for most training situations, a continuous schedule of reinforcement is a simple, efficient and powerful tool to effectively communicate with our pets. Some specific training situations might be good candidates for partial schedules of reinforcement. In those situations, you should remember to follow each bridge with a backup reinforcer, plan your training well and keep the reinforcement rate high enough for the animal to remain engaged. Have fun with your training!

Bailey, B., Bailey, M., (1998). "Clickersolutions Training Articles - Ratios, Schedules - Why And When". Clickersolutions.com. N.p., Accessed 2 February 2018.

Chance, P. (2003). Learning and behavior (5th ed.). Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth.

Kazdin, A. (1994). Behavior modification in applied settings (5th ed.). Belmont: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Martin, S., Friedman, S.G., (2011, November). Blazing clickers. Paper present at Animal Behavior Management Alliance conference, Denver. Co.

Pryor, K. (2006). Reinforce Every Behavior?. Clickertraining.com. Retrieved 2 February 2018, from https://clickertraining.com/node/670

Schunk, D. (2012). Chapter 3: Behaviorism. In Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed., pp. 71-116). MA: Pearson.

Wood, S., Wood, E., & Boyd, D. (2005). The world of psychology (5th ed., pp. 180-190). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonhighered.com/samplechapter/0205361374.pdf

Picture: www.morguefile.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed